There are reasons to be optimistic that innovative accounting firms will exploit new business models using existing technology to automate many services, freeing up labour to support more value-added activities, thereby enabling higher rates of productivity growth, writes Thomas Aubrey.

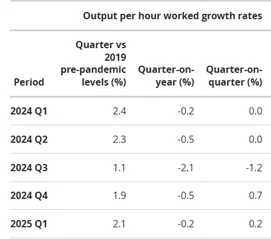

The UK’s GDP growth was higher than expected at 0.7% for Q1 2025, following growth of just 0.1% during the last quarter of 2024. Despite this somewhat positive news, the most recent flash estimates show quarter on quarter productivity growth of just 0.2% due to the rising number of hours worked. Furthermore, the quarter on year growth is still in negative territory at -0.2%.

Table 1: Flash estimates of Labour productivity

Source: ONS

As the government has made growth its central mission the slower productivity trend should be a cause for concern. Indeed, between 2019 and Q1 2025, productivity has only grown at 0.4% per annum – a far cry from the 2.6% per annum growth between 1997 and 2006. Furthermore, a disaggregation of the contribution by sectors reveals that this positive performance has largely been driven by the public sector. But it is private sector growth that is central in raising real wages and living standards, thereby sustaining the provision of key public services.

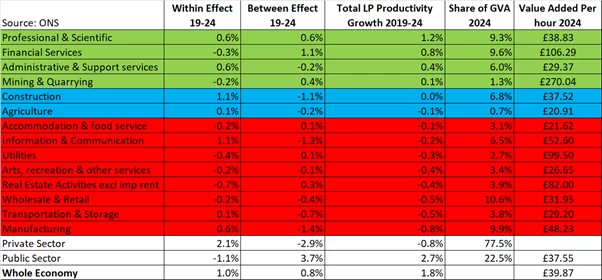

Table 2 shows that while the productivity of activities within the private sector grew by 2.1% between 2019 and 2024 (known as the ‘within effect’) this growth was cancelled out by a significant negative ‘between effect’ mostly caused by labour reallocation. Furthermore, more than half of the private sector’s activities contributed negatively to the economy (in red), including high value sectors such as Information & Communication, and Manufacturing.

On the plus side Financial Services continued to perform well – something that the UK has been traditionally strong at, alongside Professional & Scientific services, which has experienced positive growth in both the within and between effects (in green).

Table 2: Sectoral productivity disaggregation 2019 – 2024[1]

Source: ONS

Due to ongoing issues with the Labour Force Survey, the data at this high level does not provide much insight into what is driving this pattern, as each subsector will have quite different dynamics. This has lessons for the government’s industrial strategy which appears to have strait-jacketed itself into focusing on a handful of sectors – some of which are incredibly broad such as Advanced Manufacturing.

The Professional & Scientific sector breaks down into a number of diverse subsectors which have little in common with each other. Table 3 demonstrates that while these subsectors have experienced rapid growth in real GVA throughout the period, their value added per hour is starkly different.[2] This reflects the level of skill in providing services that are in demand combined with their ability to use technology.

Of the four high value sub-sectors (in green), growth in Legal & Accounting Activities given its size could potentially provide a significant contribution to overall UK productivity, particularly as this subsector may be able to benefit more from existing rather than new technologies.

Table 3: Professional & Scientific Subsectors

Source: ONS

One key driver of growth is when firms figure out how to use technology to create a competitive advantage. This is also why there tends to be a significant lag between the arrival of new technologies and the growth that results from it– hence Robert Solow’s famous paradox that “you can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics”.

Legal & Accounting Activities that rely on personal relationships and hourly billing based on the amount of labour allocated to a task are unlikely to experience much growth in productivity until firms develop new business models and disrupt the incumbents. This is largely what happened in the retail sector from the 1960s as supermarkets figured out how to compete with local shops by providing scale and letting shoppers fill their own baskets requiring fewer people, and hence lower prices.

Traditional accounting firm margins are now coming under threat from new disruptors as the bulk of the work of accountants such as the checking and processing of client data can be automated using existing technology. Software is now being rapidly deployed that links to business bank accounts, thereby enabling the automatic generation of reports and accounts in real time. Digitisation, and a greater online presence as opposed to having multiple high street offices, have also facilitated scale – enabling new entrants to overcome the constraints of local geography.

These pioneering accounting firms have also moved away from the tyranny of hourly billing to provide bundled services using transparent and value-based pricing which makes them much more competitive. This is also freeing up human capital to perform more value-added services – similar to the shift in the banking sector when it deployed ATM machines freeing up staff.

As these new online accounting firms are rapidly scaling up, they have tended to focus on serving the lower end of the market where there is a lot of demand and the services demanded are relatively straight forward to automate. There are 5.5 million (m) businesses in the UK of which 74% are non-employers which includes sole traders and director owned firms. In addition, many micro firms of which there are an additional 1.2m, may also fall into the category of being relatively straightforward to service.

Once innovative firms pick off the lowest segment of a market, they can build on this platform to target higher value segments. For example, in the 1950s Britain was the leading exporter of motorbikes, but by the 1970s Britain was importing ten times more motorcycles than it exported. Japanese firms initially targeted the lower segments of the market with cheaper and more lightweight products before becoming dominant across the entire market, which was one of the reasons why the entire UK industry collapsed.[3]

As businesses increasingly trust these new accountancy entrants to provide quality but largely automated services, they will switch from more expensive, traditional providers. Hence, it is not unreasonable to expect these new online accounting firms will – in time – fundamentally transform the sector, eliminating traditional providers in the process of creative destruction, as was famously argued by Joseph Schumpeter. While this might not be good news for the firms left behind, it will be good for the UK economy.

[1] The sectoral disaggregation uses GEAD (Generalized Exactly Additive Decomposition) based on Tang & Wang (2004). The ‘within’ effect is productivity growth in activities within the sector whereas the ‘between’ effect measures the change in relative size of sectors taking into account the reallocation of labour between sectors and changes in real output prices. e = estimated as ONS does not publish these values.

[2] The latest available data is from 2022.

[3] See The Strange Death of the British Motorcycle Industry. Koerner 2012.

The views and opinions expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the Bennett Institute for Public Policy.